What Is Linux

Linux is an open-source operating system like other operating systems such as Microsoft Windows, Apple Mac OS, iOS, Google android, etc. An operating system is a software that enables the communication between computer hardware and software. It conveys input to get processed by the processor and brings output to the hardware to display it. This is the basic function of an operating system. Although it performs many other important tasks, let's not talk about that.

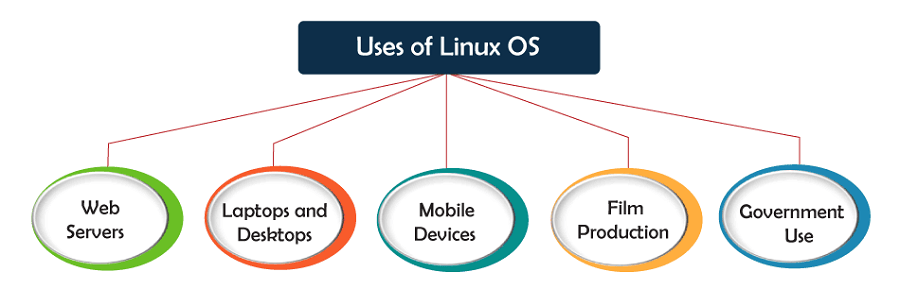

Linux is around us since the mid-90s. It can be used from wristwatches to supercomputers. It is everywhere in our phones, laptops, PCs, cars and even in refrigerators. It is very much famous among developers and normal computer users.

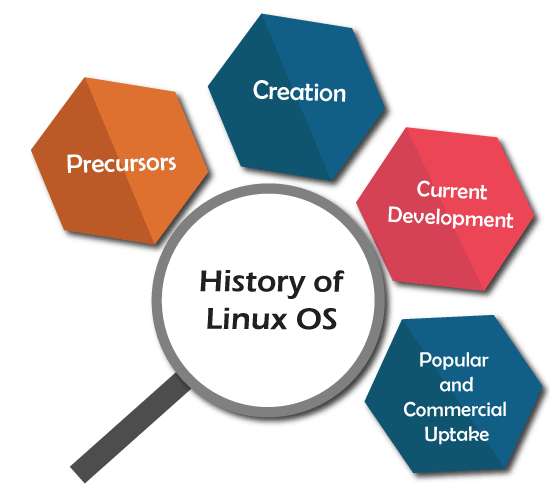

Evolution of Linux OS

The Linux OS was developed by Linus Torvalds in 1991, which sprouted as an idea to improve the UNIX OS. He suggested improvements but was rejected by UNIX designers. Therefore, he thought of launching an OS, designed in a way that could be modified by its users.

Nowadays, Linux is the fastest-growing OS. It is used from phones to supercomputers by almost all major hardware devices.

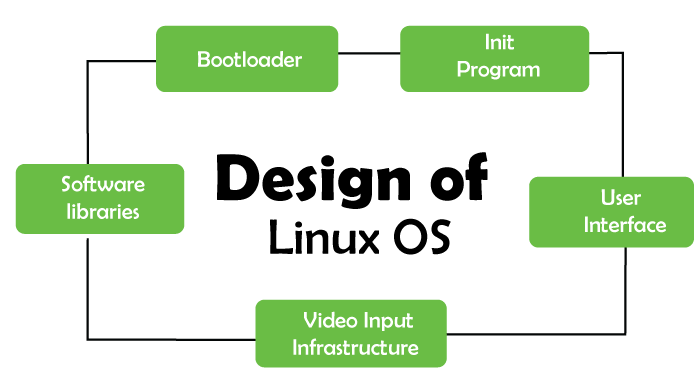

Structure Of Linux Operating System

An operating system is a collection of software, each designed for a specific function.

Linux OS has following components:

1) Kernel

Linux kernel is the core part of the operating system. It establishes communication between devices and software. Moreover, it manages system resources. It has four responsibilities:

- device management: A system has many devices connected to it like CPU, a memory device, sound cards, graphic cards, etc. A kernel stores all the data related to all the devices in the device driver (without this kernel won't be able to control the devices). Thus kernel knows what a device can do and how to manipulate it to bring out the best performance. It also manages communication between all the devices. The kernel has certain rules that have to be followed by all the devices.

- Memory management: Another function that kernel has to manage is the memory management. The kernel keeps track of used and unused memory and makes sure that processes shouldn't manipulate data of each other using virtual memory addresses.

- Process management: In the process, management kernel assigns enough time and gives priorities to processes before handling CPU to other processes. It also deals with security and ownership information.

- Handling system calls: Handling system calls means a programmer can write a query or ask the kernel to perform a task.

2) System Libraries

System libraries are special programs that help in accessing the kernel's features. A kernel has to be triggered to perform a task, and this triggering is done by the applications. But applications must know how to place a system call because each kernel has a different set of system calls. Programmers have developed a standard library of procedures to communicate with the kernel. Each operating system supports these standards, and then these are transferred to system calls for that operating system.

The most well-known system library for Linux is Glibc (GNU C library).

3) System Tools

Linux OS has a set of utility tools, which are usually simple commands. It is a software which GNU project has written and publish under their open source license so that software is freely available to everyone.

With the help of commands, you can access your files, edit and manipulate data in your directories or files, change the location of files, or anything.

4) Development Tools

With the above three components, your OS is running and working. But to update your system, you have additional tools and libraries. These additional tools and libraries are written by the programmers and are called toolchain. A toolchain is a vital development tool used by the developers to produce a working application.

5) End User Tools

These end tools make a system unique for a user. End tools are not required for the operating system but are necessary for a user.

Some examples of end tools are graphic design tools, office suites, browsers, multimedia players, etc.

Why use Linux?

This is one of the most asked questions about Linux systems. Why do we use a different and bit complex operating system, if we have a simple operating system like Windows? So there are various features of Linux systems that make it completely different and one of the most used operating systems. Linux may be a perfect operating system if you want to get rid of viruses, malware, slowdowns, crashes, costly repairs, and many more. Further, it provides various advantages over other operating systems, and we don't have to pay for it. Let's have a look at some of its special features that will attract you to switch your operating system.

Free & Open Source Operating System

Most OS come in a compiled format means the main source code has run through a program called a compiler that translates the source code into a language that is known to the computer.

Modifying this compiled code is a tough job.

On the other hand, open-source is completely different. The source code is included with the compiled version and allows modification by anyone having some knowledge. It gives us the freedom to run the program, freedom to change the code according to our use, freedom to redistribute its copies, and freedom to distribute copies, which are modified by us.

In short, Linux is an operating system that is "for the people, by the people."

And we can dive in Linux without paying any cost. We can install it on Multiple machines without paying any cost.

It is secure

Linux supports various security options that will save you from viruses, malware, slowdowns, crashes. Further, it will keep your data protected. Its security feature is the main reason that it is the most favorable option for developers. It is not completely safe, but it is less vulnerable than others. Each application needs to authorize by the admin user. The virus cannot be executed until the administrator provides the access password. Linux systems do not require any antivirus program.

Favorable choice of Developers

Linux is suitable for the developers, as it supports almost all of the most used programming languages such as C/C++, Java, Python, Ruby, and more. Further, it facilitates with a vast range of useful applications for development.

Developers find that the Linux terminal is much better than the Windows command line, So, they prefer terminal over the Windows command line. The package manager on Linux system helps programmers to understand how things are done. Bash scripting is also a functional feature for the programmers. Also, the SSH support helps to manage the servers quickly.

A flexible operating system

Linux is a flexible OS, as, it can be used for desktop applications, embedded systems, and server applications. It can be used from wristwatches to supercomputers. It is everywhere in our phones, laptops, PCs, cars and even in refrigerators. Further, it supports various customization options.

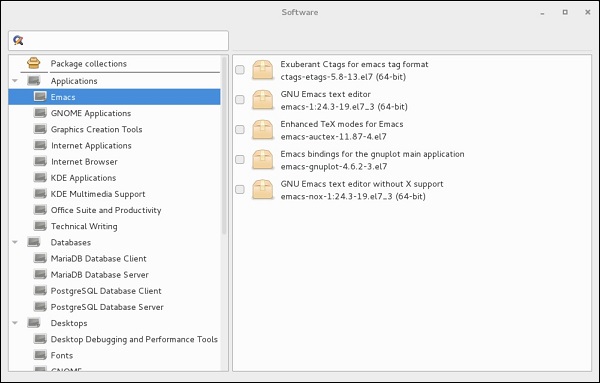

Linux Distributions

Many agencies modified the Linux operating system and makes their Linux distributions. There are many Linux distributions available in the market. It provides a different flavor of the Linux operating system to the users. We can choose any distribution according to our needs. Some popular distros are Ubuntu, Fedora, Debian, Linux Mint, Arch Linux, and many more.

For the beginners, Ubuntu and Linux Mint are considered useful and, for the proficient developer, Debian and Fedora would be a good choice. To Get a list of distributions, visit Linux Distributions.

How does Linux work?

Linux is a UNIX-like operating system, but it supports a range of hardware devices from phones to supercomputers. Every Linux-based operating system has the Linux kernel and set of software packages to manage hardware resources.

Also, Linux OS includes some core GNU tools to provide a way to manage the kernel resources, install software, configure the security setting and performance, and many more. All these tools are packaged together to make a functional operating system.

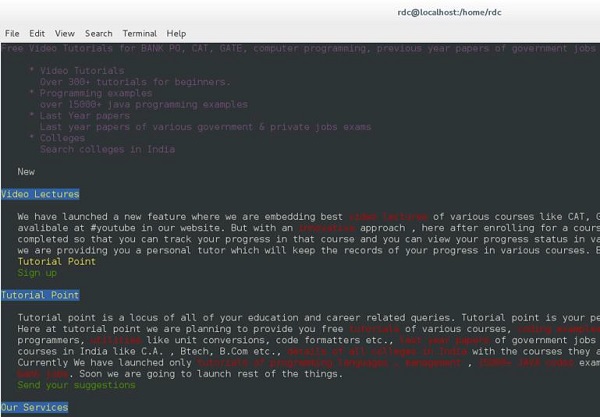

How to use Linux?

We can use Linux through an interactive user interface as well as from the terminal (Command Line Interface). Different distributions have a slightly different user interface but almost all the commands will have the same behavior for all the distributions. To run Linux from the terminal, press the "CTRL+ALT+T" keys. And, to explore its functionality, press the application button given on the left down corner of your desktop.